By Gabe Rivin

Powderhouse Studios won’t be like most high schools.

It’s not just the 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. schedule or the lack of homework. It’s far more than the school’s banishing of traditional grade levels.

What’s perhaps most distinctive is the way it will respond to a central question in education today: Who should control the learning in class? For Powderhouse, the answer is simple.

It’s all about the students.

Powderhouse Studios, a public high school slated to open the fall of 2018 in Somerville, Massachusetts, is distinctly oriented around personalization. When the students arrive, they’ll largely pursue the subjects they’re interested in — not what they’re told they have to learn. They’ll do so through ambitious projects, from writing screenplays to building robots. Teachers will act more like support staff than authority figures.

[quote position="full" is_quote="false"]With its overhaul of the way students learn, Powderhouse is aiming to show that schools can better respond to struggling and low-performing students.[/quote]

“It’s very clear that not everyone should learn the same stuff and won’t learn it in the same way,” says Alec Resnick, the school’s director. “What matters to us is setting up an environment where we can respond to what people are interested in and what people need.”

For many of us, the one-size-fits-all approach is all we’ve experienced in schools. Whether the subject is the Great Depression or polynomials, the majority of students show up to class and are told what they’re going to learn and how they’re going to learn it. There’s not much choice in the matter.

With little sense of agency over their learning, students can grow disengaged.

“If somebody’s not engaged, they won’t learn,” Resnick says.

Rigorous, project-based learning can help remedy this situation. This form of education situates students at the center of their own learning. It increases performance by engaging students in complex tasks with real-world applications. Doing so can dramatically increase students’ sense of ownership over their learning and thereby increase their engagement in class.

“When children and youth have a question or problem they’re trying to solve, they have a reason to read, they have a reason to write, and they have a reason to be strategic in their reading and writing because they want to be efficient,” says Elizabeth Birr Moje, the dean of the University of Michigan’s education school and an expert in project-based learning.

Moje and others have seen this effect firsthand in Detroit, where students have shown meaningful gains in achievement with project- and inquiry-based learning.

“We know that this is how people learn best,” she says.

This can be particularly important for struggling students. One highly cited study notes that project-based learning can not only help remedy students’ boredom, it can make schoolwork more meaningful and boost performance.

This approach is what’s driving Powderhouse Studios. Whether students are writing a political speech or developing a website, they’ll do work that matters to them and that feels purposeful — the kind of work that takes place in the real world.

How, though, will 14-year-olds know where to start?

Powderhouse students will work in small seminar-like classes alongside three staff members — a project manager, curriculum developer, and social worker. These staff members will help students identify and develop their interests. They’ll also monitor students’ well-being and help them design the ambitious, academically rigorous projects that follow from their interests.

Students’ projects will hit the usual subject areas. A 3-D rendering project might rely on visual art and geometry, for example. A marketing campaign could rely on language arts and statistical research. After graduating, students will still be equipped with the kind of learning that Massachusetts expects of high school graduates.

And Powderhouse students will likely graduate with fewer bags under their eyes. Knowing that adolescents are biologically programmed to sleep later, Powderhouse staff decided to start the school day at 10 a.m. rather than the earlier start times that can harm student achievement.

The school year will be 220 days, too, helping to stave off the notorious summer-learning losses that accrue from days spent at movie theaters. And rather than clustering students by age in traditional grades, Powderhouse will cluster students with different skills and interests, where they’ll learn from each other in seminar-like classes.

“What we’re doing looks much more like a Ph.D. program or an M.F.A. program,” Resnick says, noting that many of the school’s nontraditional methods have been given the green light thanks to Massachusetts’ Innovations Schools initiative.

Resnick acknowledges that Powderhouse Studios is not for everyone. Some students prefer a larger, more traditional high school.

Still, as Powderhouse continues to grow, it could pose an interesting, more broad question for educators and parents alike: How many of us would have learned more and enjoyed classes if we’d had the chance to attend a school like Powderhouse?

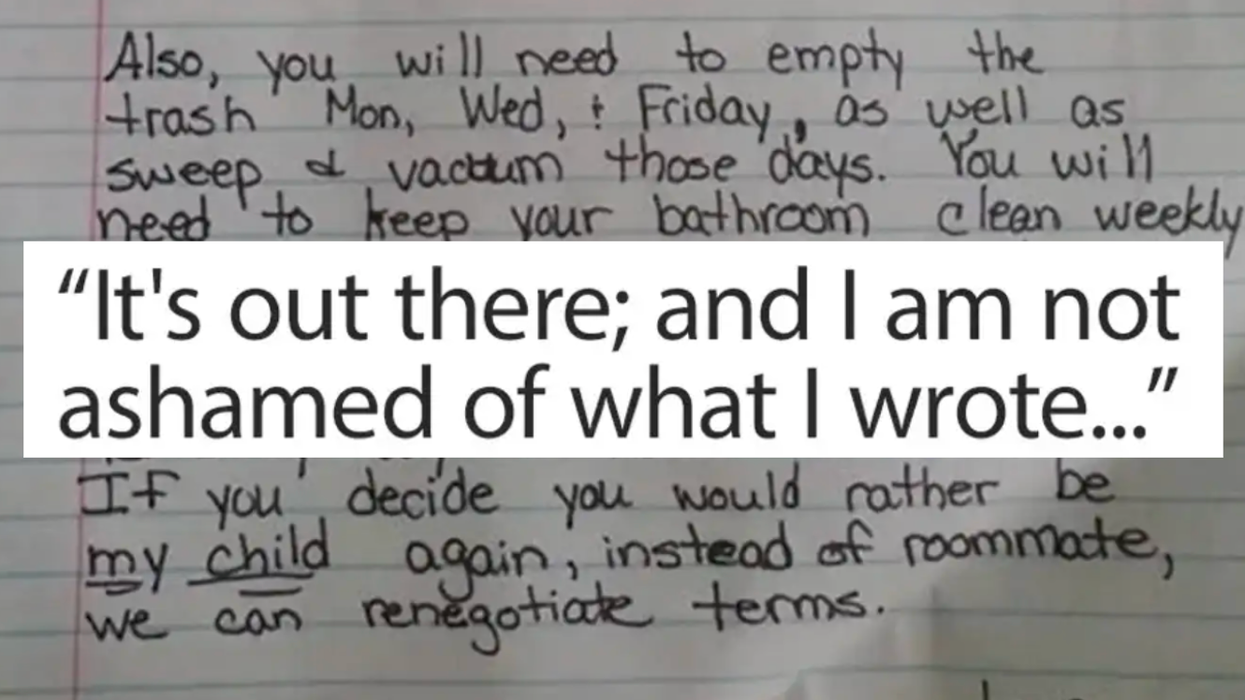

A real estate agent talks with a young coupleCanva

A real estate agent talks with a young coupleCanva A frustrated school teacher takes a breakCanva

A frustrated school teacher takes a breakCanva A young girl plays around in her messy roomCanva

A young girl plays around in her messy roomCanva

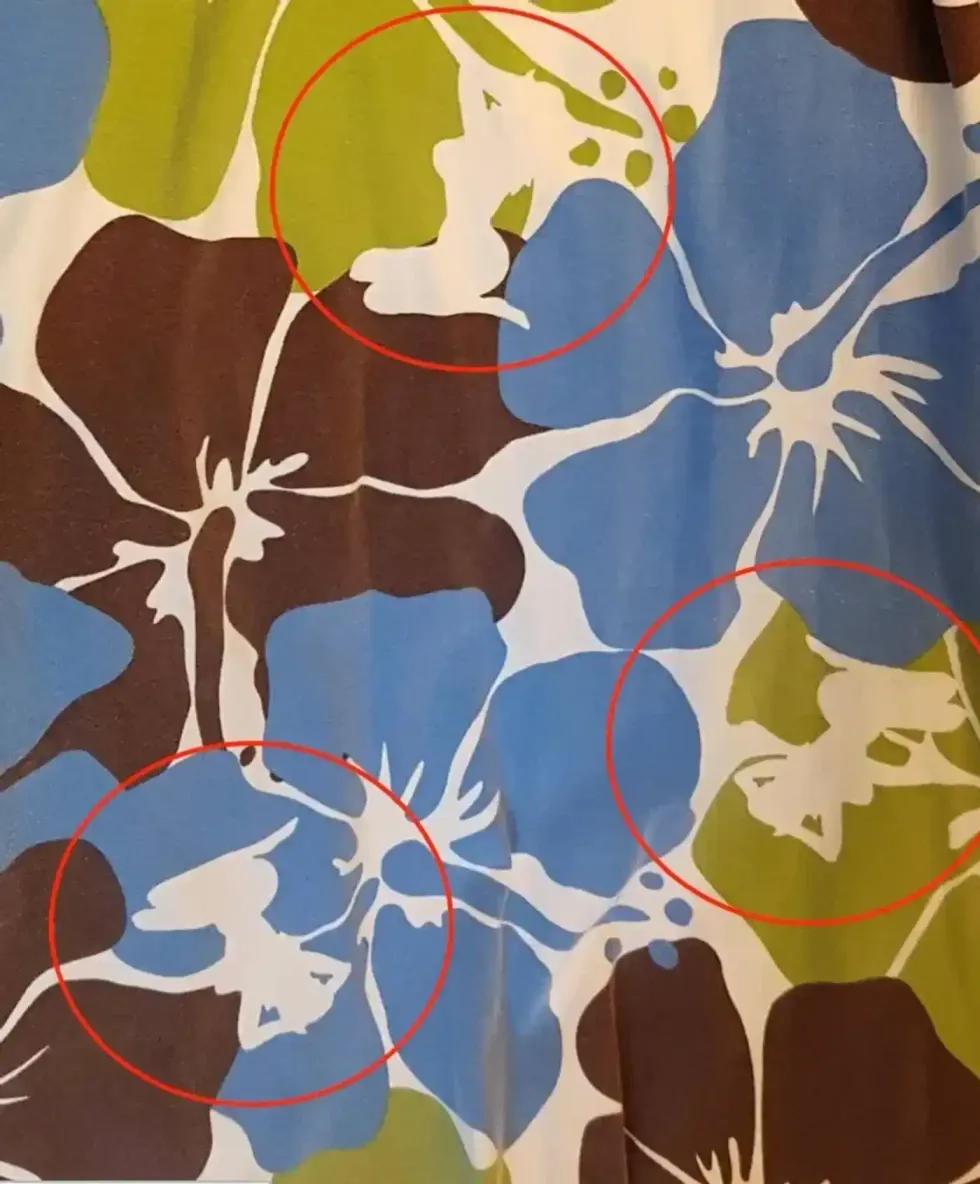

Image of the floral dress with the risque images circled

Image of the floral dress with the risque images circled  Gif of Tim Robinson via

Gif of Tim Robinson via

Gif of Kaitlin Olson saying "Because I said so ... that's why" via

Gif of Kaitlin Olson saying "Because I said so ... that's why" via

A hand holds several lottery ticketsCanva

A hand holds several lottery ticketsCanva "Simpsons" gif of newscaster winning the lotto via

"Simpsons" gif of newscaster winning the lotto via