For Carlos Rodriguez, CEO of the Community FoodBank of New Jersey, the spike in demand has been as dramatic as the arrival of the coronavirus. In a normal year, Rodriguez's organization provides food for some 50 million meals through a network of 1,000 pantries, food kitchens and other affiliates.

But the pandemic meant that some of his bigger food pantries saw 50% more traffic almost overnight. And people who had previously donated food were now, for the first time in their lives, asking for help feeding their families.

The disaster-like level of need is only one problem. Panic shopping by consumers has left grocery stores with little left over to donate, Rodriguez said, leaving the Community FoodBank without its most reliable supply of provisions. To keep feeding its clients, he said, his organization has been forced to vie with national grocery chains to buy basic items, paying 15% more than only a month or so ago.

Rodriguez estimates the Community FoodBank has clear access to about two and a half weeks of food. "I have to tell you, we are week by week," he said. "The need keeps compounding."

Around the country, as more than 16 million people have filed for unemployment in just three weeks, the nation's emergency assistance food supply chain has come under rapid strain. Food banks are besieged by unprecedented traffic, even as the pandemic reduces the number of volunteers who help staff the operations. Supplies are harder to come by as consumers stock up more and donate less.

The result, in some cases, has been dramatic: hourslong waits for donated food. Images of multi-mile lines of idling cars are becoming the modern equivalent of the Depression-era photos of men in overcoats waiting for bread.

Calls into some food assistance hotlines have increased tenfold, said Katie Fitzgerald, executive vice president and chief operating officer for Feeding America, the nation's largest food bank organization. Between 30% and 50% of the visitors to food banks in Feeding America's network since the coronavirus are seeking food assistance for the first time, she said. "There's a lot of desperation and fear out there."

Data from state 211 help lines, which help connect Americans with social services, tell a similar story. Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis compared requests for food pantry information on 211 calls between March 12 and 25 to the same period last year. Those requests at least doubled in all 23 states the researchers examined. In New Jersey, 211 food pantry requests jumped 2,200%; in Alabama, 967%; and in Maryland, 963%.

In March, thousands more people than usual called into 211 help lines looking to find local food pantries, according to data from 29 states.

Local food banks are under duress. The United Food Bank in Mesa, Arizona, served roughly four times as many families in the last full week of March compared with the first week, all while battling a 40% reduction in grocery store food donations, said Tyson Nansel, the organization's spokesperson.

The consequences have been immediate. A fifth of local meal assistance programs in Feeding America's network have already shuttered at least temporarily, according to a survey of the organization's food banks.

The overall U.S. food supply, experts say, is plentiful. But a burst in demand because of pandemic fears has led to temporarily empty shelves, said Ananth Iyer, department head of management at Purdue University and an expert on supply-chain management.

That has reduced food bank supplies since unsold food with expired "sell by" or "best by" dates in grocery stores, which can still be safe to eat, is often donated to food banks. Cash donations help food banks, but Fitzgerald said it's still tough to purchase shelf-stable supplies right now.

In the survey of her 200-bank network, Fitzgerald said, 20% worry they'll run out of the necessary supplies in the next two to four weeks. "We estimate that there is a $1.4 billion gap in what the emergency food assistance system needs to meet this elevated need," she said. Without that, Fitzgerald said, the organization may have trouble sustaining operations. "It's a very big problem."

Meanwhile applications for the federal government's largest food-support program, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP — colloquially referred to as food stamps — are rising in most states, said Stacy Dean, vice president for food assistance policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, signed into law March 18, lets states increase benefits (with approval by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees the SNAP program and gives guidance to state agencies and local offices administering it) for households not already receiving maximum SNAP benefits.

Pharmacy Workers Are Coming Down With COVID-19. But They Can't Afford to Stop Working.As prescriptions surge, Walgreens and CVS employees say they need more protective gear, cleaning supplies and sick pay. "Someone will come into work sick and there's nothing anyone can do about it," a pharmacist says.

This gives no boost to the poorest families, who already receive maximum benefits, according to Dean. "I'm very disappointed that they locked out the poorest families from emergency allotments," she said. Dean and other advocates say the USDA could do more.

Under the Families First act, SNAP households are receiving a total of $1.7 billion each month above the previous total, the USDA said in an emailed response. The agency added that it is "leveraging all of our programs' services, built-in flexibilities, and new flexibilities to ensure people have access to food."

The USDA estimates that some 37 million Americans were food insecure in 2018. An additional 17 million people are now at risk of going hungry, according to projections by Feeding America.

SNAP applications are rising in states such as Georgia, Utah, Louisiana and Connecticut. In Alabama, online applications for food stamps spiked 155% from February to March. California's applications more than doubled between the first and fourth weeks of March.

In many states, there are fewer staff processing more applications, because of social distancing and coronavirus-related telework, Dean said. In California, Los Angeles County's Department of Public and Social Services closed its offices and expanded teleworking, according to spokesperson James Bolden. He said that the department hasn't heard about issues with its online portal, but that some customers have had longer-than-usual wait times for its telephone Customer Service Center.

The Families First act was intended to be an immediate relief response, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities wrote in a recent post. The package includes other benefits, like one piece that lets states (with the USDA's signoff) give meal-replacement benefits to households with children who'd otherwise receive free or reduced-price meals at school. States, including Michigan and Florida, are starting to get approved for this.

On April 6, 140 representatives — all but one a Democrat — signed a letter to House and Senate leaders urging them to increase the maximum SNAP benefit by 15%, bump up the monthly minimum benefit from $16 to $30 and put a hold on Trump administration rules that would weaken benefits and eligibility for food stamps.(The 2009 Recovery Act increased the maximum monthly SNAP benefit by 13.6%.)

Charitable groups like Feeding America have called for a boost to SNAP to aid the millions of newly unemployed Americans, calling it the best short- and long-term solution to help food access.

In most states, SNAP benefits can't be used to make online food purchases, though a pilot program has opened up this option in a handful of states. It hasn't yet made it to Virginia, where the roadblock has frustrated recipients of food stamps like Erika Schneider, a 42-year-old in Charlottesville who is unemployed because of a respiratory and neurological condition. Schneider, who doesn't drive, started a Change.org petition to broaden online grocery delivery and pickup options for SNAP users.

She relied on daily Meals on Wheels food delivery, which stopped daily deliveries a few weeks ago and instead has been dropping off shelf-stable items every two weeks. Schneider is on a special diet and said she couldn't eat everything that was dropped off recently. She resorted to eating cans of plain tomato sauce and rice. "All of a sudden, I was like, 'Oh my god, I'm almost out of food,'" Schneider said. "And then I ran out of food and completely panicked."

She was finally able to restock her cupboards with the help of community donations and organizations, she said, and a few days ago, Meals on Wheels dropped off a box of food.

"I guess I just got lucky this time," Schneider said. "But we shouldn't have to get lucky in a crisis. We should have the infrastructure for equal access to food at any time."

This story was originally published by Pro Publica and was written by Beena Raghavendran and Ryan McCarthy.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

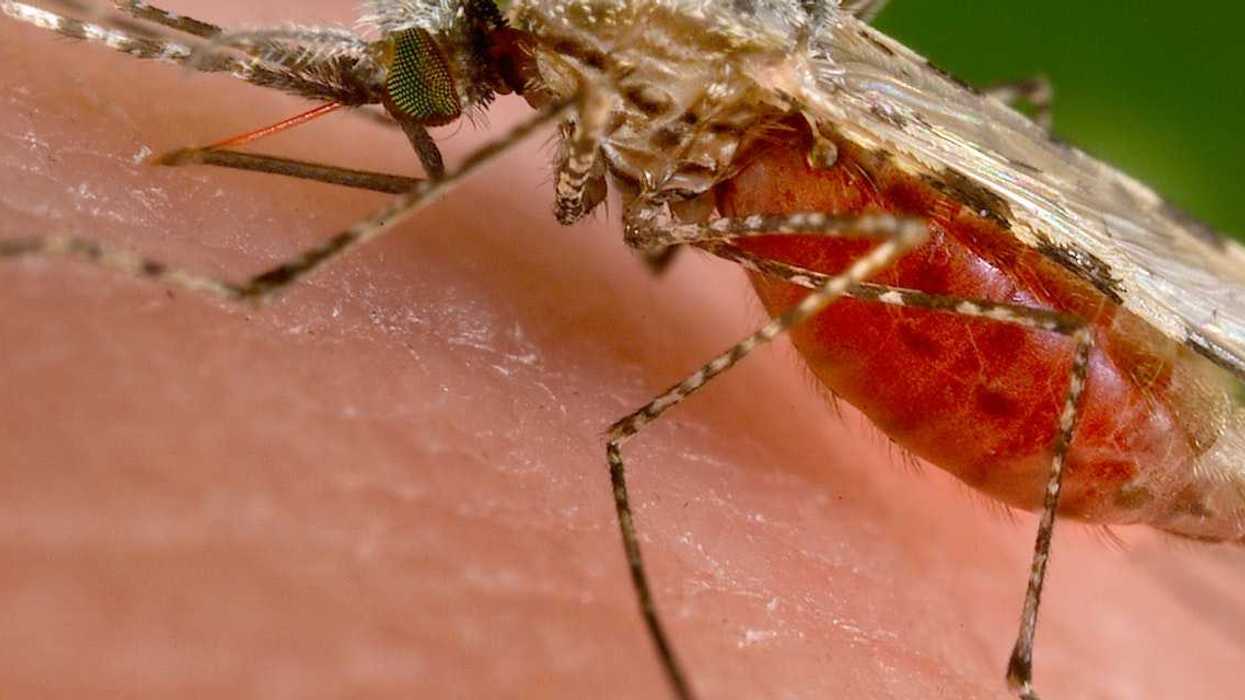

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

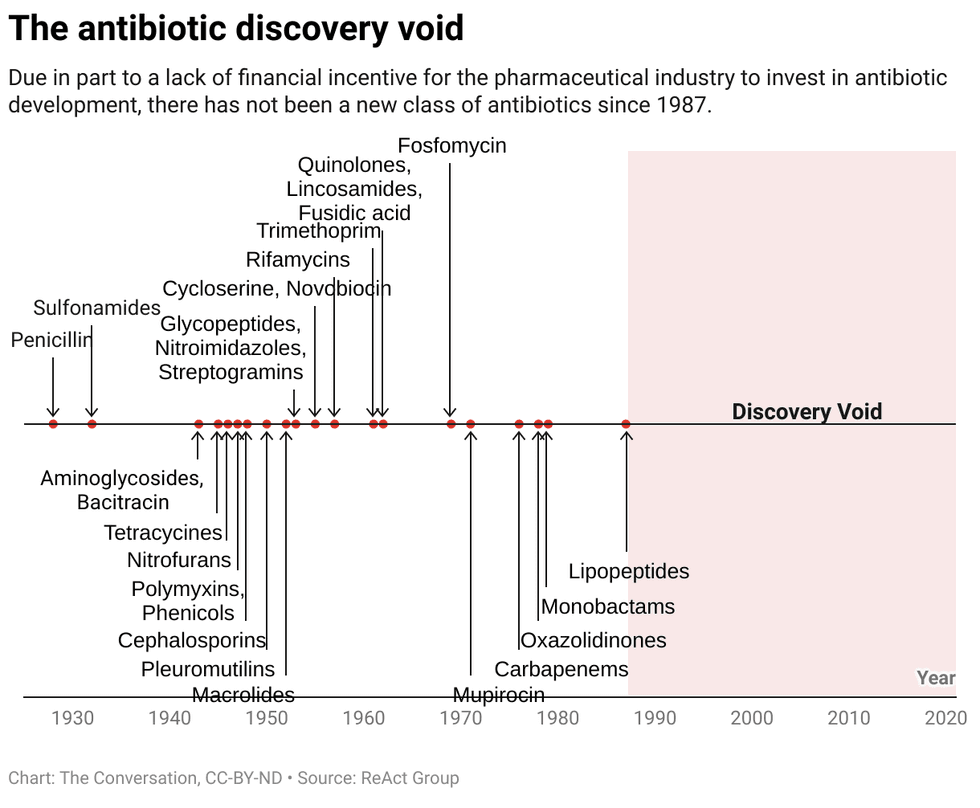

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

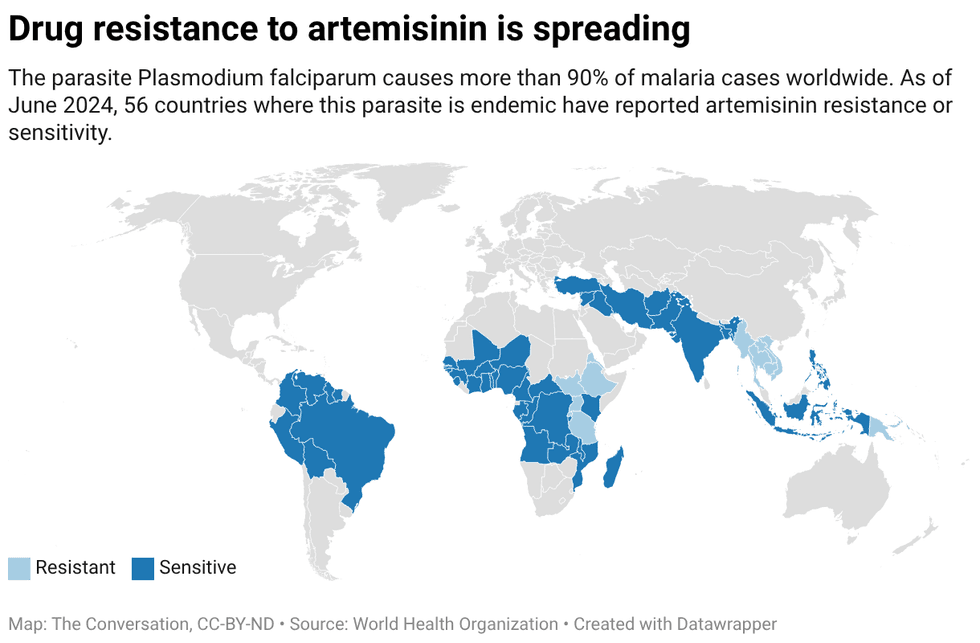

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely. Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.