Stop me if you’ve heard this one, but Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha might have been a great stand-up comic in another life. Seeking enlightenment in Nepal circa 525 B.C. didn’t give the namesake of the 1922 spiritual Bildungsroman much chance to develop an act, but Hesse’s description of his protagonist’s inner struggle could easily be applied to every clown caught crying, from Pagliacci to Louis C.K.: “He brought everyone joy; he pleased everyone. However, Siddhartha didn’t bring himself joy; he didn’t please himself.” This “seed of discontent” sprouting within him leads Hesse’s hero to join an order of self-denying proto-Buddhist monks who fast and meditate in the woods, but he soon becomes disillusioned with their practice and insights gained. “I could have learned it in any pub located in the whore’s district, there among the manual laborers and the gamblers,” he complains.

This route to self-discovery comes closer to the road traveled by more modern truth-seekers, comedians—legendary comic Lenny Bruce, for example, who probably did his best onstage act philosophizing as a strip-club MC. What Hesse suggests, decades before the rise of open mics and the two-drink minimum, is that the meditating monks and boozing barflies are actually seeking and achieving the same thing: “a brief escape out of the agony of self-existence … a momentary anesthetic against the pain and meaninglessness of life.” Bruce, who died of a morphine overdose, clearly sought the same. “After throwing needed light into America’s dark places,” critic Walter Goodman concludes, “by age 40 Lenny Bruce had nothing left to lighten the darkness of his final years.” Something similar could perhaps be said of each of the many talented comics who have since died of drug overdoses (Mitch Hedberg, Greg Giraldo) or outright suicide (Freddie Prinze, Richard Jeni, Robin Williams).

According not only to anecdotes about those high-profile comedic acts but also to a study published last year in the British Journal of Psychiatry (which has been often cited following Williams’ death in 2014), comedians may be particularly prone to suffering mental illnesses and distress. The study gathered the answers of more than 500 self-identified comedians responding to the “Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences … with scales measuring four dimensions of psychotic traits.” The comics reported higher instances of all four traits than the control group. Of the four traits, comedians were most likely to report cognitive disorganization (writes Hesse of Siddhartha: “Dreams and restless thoughts came flowing to him out of the river’s water, twinkled to him from the stars of the night, melted out of the sunbeams”) and introvertive anhedonia, defined as the inability to experience pleasure from social interactions and physical contact (“Everything was a lie, everything stank, everything stank of lies, everything feigned meaning and happiness and beauty, and yet everything was decaying while nobody acknowledged the fact. The world tasted bitter; life was agony.”).

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]Sometimes I come home from shows...and I’ve been more upset than when I started because I’m taking on all these things to be angry about.[/quote]

“Comedians are especially susceptible to wanting to quote-unquote ‘kill the pain,’” confirms comic Eddie Pepitone, “[You] live a stressful life, [you] travel and try to have relationships and meaning [while] dealing with audiences that don’t like you.” Pepitone is one of the growing number of stand-ups following in Bruce’s footsteps artistically while relying on coping methods closer to those of Siddhartha’s monks. Best known to mainstream audiences for his small but memorable role in Old School, or his appearances as Conan O’Brien’s recurring heckler, Pepitone, who describes his manic, stream-of-consciousness act as “almost like one long, 30-year primal scream,” seems to embody the comic’s mental plight. “One of my constant thoughts that I’m obsessed with all the time is that I’m not successful enough, that people don’t respect me enough,” he says. “I just go in this mental loop of feeling neglected and not validated and not cared for, and it’s just like I have to work every day to get out of that horrible loop of thinking that keeps me stuck in such a petty thought pattern.”

If that sounds like a particularly eloquent self-assessment, it’s because Pepitone has had plenty of practice reflecting on his mental state, both in professional treatment for anxiety and as a guest on podcasts such as Paul Gilmartin’s appropriately titled The Mental Illness Happy Hour. The title of his own podcast, Pep Talks with the Bitter Buddha, comes from the nickname given Pepitone by another comic, who was tickled to learn that the Staten Island screamer had taken up meditation in his 50s. On the show, Pepitone frequently talks not only about meditation, but also about the ideas and philosophies of The Power of Now author Eckhart Tolle, Buddhist lecturer Jack Kornfield, and other like-minded thinkers. Though Pepitone is known for his rants, these are rarely one-sided conversations. His guests are drawn from a large pool of comedians (such as Duncan Trussell, whose own podcast is as likely to feature an actual monk as it is another comic) eager to not only air their psychic suffering, but also their Eastern philosophy-influenced salves. “I think the reason meditation and The Power of Now and stuff like Jack Kornfield seem new to comedy is there’s more of an awareness of mental illness,” says Pepitone. “It’s just an evolution. Years ago people weren’t talking about this stuff ... but now comedians are reaching out for some help. The high-profile mental illness of a guy like Robin Williams also raises awareness about ‘Oh shit, maybe I need some techniques to deal with all this stuff.’”

The authors of the British Journal of Psychiatry study offered an explanation for why a mild form of mental illness—or at least exhibiting some of its symptoms—might be oddly beneficial to a comic. The racing, wildly disparate thoughts associated with paranoid schizophrenia, for example, might aid a performer in developing an original perspective. But after the audience heads for the exits, that performer is left to live alone in that addled headspace every other hour of the day. And when the comic’s sense of humor—an otherwise, according to the study’s authors, “healthy and desirable trait” and potential “coping strategy”—is also his or her primary income source, it’s at least as likely to cause stress as it is to relieve it. For Pepitone—whose better-known bits include heckling himself with a hilariously specific list of his own phobias and neuroses and channeling fears fueled by bleak reads like Chris Hedges’ Empire of Illusion into throat-shredding absurdist theater comedy—his creative output can function like a “release valve.” Getting as heated as he does on stage, however, can sometimes only increase his internal pressure. “Sometimes I come home from shows,” he confesses, “and I’ve been more upset than when I started because I’m taking on all these things to be angry about.”

Maria Bamford—who uses her hyperactive energy and ability to embody multiple personalities to great comedic effect in roles ranging from a recovering methadone addict (Arrested Development’s Debrie Bardeaux), to pretend princesses (Adventure Time), to the “Crazy Target Lady” in a popular series of holiday TV ads—has also discussed her struggles with anxiety and other mental-health issues extensively both on and off stage. She named her 2009 album Unwanted Thoughts Syndrome, after the phrase she coined to describe the version of obsessive-compulsive disorder she suffers from. Along the same lines, her 2012 The Special Special Special! includes bits about Bamford checking herself into a hospital for psychiatric treatment when she became suicidal, as well as her family’s lovingly inept responses to her depression.

In addition to these issues, Bamford, who recorded The Special Special Special! in her living room for an audience of just her parents, struggles with stage fright. “It is still a battle,” says Bamford, the subject of a profile in The New York Times Magazine that sported the headline “The Weird, Scary and Ingenious Brain of Maria Bamford” and focused mainly on her mental illness. “It is a horrifying battle. It’s not always a horrifying battle, but I am afraid. I don’t want to perform, and in fact it’s just as hard as it was in the beginning.” But despite her vicious send-ups of her life-coach sister’s affirmations, Bamford is an enthusiastic advocate of 12-step programs and self-help books and tries to see the potential ego-blow of a cold room as an opportunity for personal growth. “The nice thing about live performance is that it’s very humbling. [The audience says], ‘We paid to see this or we haven’t paid to see this and we’re going to do with it what we will.’” Not only is awareness of the subjective experience an often-preached key tenant of Buddhist philosophy, it can help balance the otherwise unbearable roller coaster of “They loved me! They hated me! They loved me!” that tempts any live performer.

Bobbie Oliver, author of the Zen-influenced The Tao of Comedy (a book recommended by Bamford) says that depression, crises of identity, and a potentially dangerous desire for the approval of others plague stand-ups at every level, from veteran “comic’s comics” like Bamford and Pepitone to the first-time comedy students that come through Oliver’s workshops. In her classes, she encourages students to use techniques like mindfulness meditation and present-moment awareness as part of the creative process. Oliver, who was “in and out of mental hospitals” from the time she was nine through the 11th grade, says that “comedians, in my experience, are usually the smartest, most damaged people in the room.” But she also views comedy as a potential healing act. “We’re constantly looking for a way to cope with life and you can find that in your craft, or you can use your craft to torture yourself. … Are you going to let it be something that nurtures you, and allows you to hear your true voice whispering to you over all the screaming in the world, or are you just going to let comedy be one more thing that you use to beat the shit out of yourself—‘How am I not famous yet? And why did that person get this show? Why don’t I have that?’ … You can use [comedy] to show you how to insert stillness into your life and write jokes about things that upset you.”

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]You can use [comedy] to show you how to insert stillness into your life and write jokes about things that upset you.[/quote]

Bitter Buddha or not, Pepitone—who rails hysterically against the ineffectual remedies offered by “New Age” friends on his 2011 album A Great Stillness (“Is sleepy-time tea going to make up for the fact that I was molested and kept in a steel box for 25 years?”)—has clearly chosen the second path. “I’ve never been a great one-liner writer,” Pepitone says, “so my comedy kind of comes from a place of ‘This is what I’m concerned about, and this is what I’m thinking about.’ For me, the comedy is my struggle against this stuff. It’s all a comedy that we’re trying to live these dignified lives in an undignified world.” Pepitone has certainly realized that his own struggles to stay sane and productive are ongoing. “What I’ve come to lately is that to be creative, you have to nurture it all the time with authors and techniques like meditation or really being present … [but] to be present in your life is really a difficult thing in a stressful world,” he says.

In this effort, comedians might have an unlikely leg up over the general, enlightenment-seeking populace. The idea that we, moment by moment, create our own world and everything in it has special relevance to a stand-up on stage, who is judged only as good as his or her last punch line, and who must sweat out seemingly interminable silence preceding the laughter. Under these conditions, intently meditating on the silence is practically an involuntary response, and fretting over the future in a notoriously competitive and often indifferent industry can be fatal—if not to the comic, then at least to the jokes. In The Power of Now, best-selling self-help author Tolle advises: “To listen to the silence, wherever you are, is an easy and direct way of becoming present.” A good comedian, so often praised for his or her onstage “presence,” is able to embrace this unpredictable present and turn it to their advantage. Bamford can even re-contextualize the bane of many a comedian’s existence, the heckler, into a moment of compassionate awareness. “I try not to think of it as heckling anymore,” she says, “It’s just that people are trying to tune in. We’re all a part of the show, we just haven’t rehearsed this yet.”

Though comedy can be cathartic, Pepitone cautions that it shouldn’t be confused with therapy. “Obviously for a guy like Robin Williams, it helped, but look what happened,” Pepitone says. “There’s a certain level of mental illness [at which] you just need professional treatment. So fuckin’ doing standup comedy doesn’t cure you, that’s for sure.” It won’t save every damaged soul drawn to the weird balance between pure ego and absolute self-surrender that it offers, but stand-up comedy gives many something other than their own worried thoughts to meditate on for the moment. And mindfulness can in turn clue comedians in to the biggest joke of all. Toward the end of Siddhartha, the title character, an old ferryman who has just attained enlightenment, tries to impress this upon to his devoted friend Govinda.

Siddhartha: “See here, Govinda, this is one of the thoughts that I’ve found: wisdom cannot be passed on. Wisdom that a wise man attempts to pass on to someone always sounds like foolishness.”

Govinda: “Are you joking?”

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

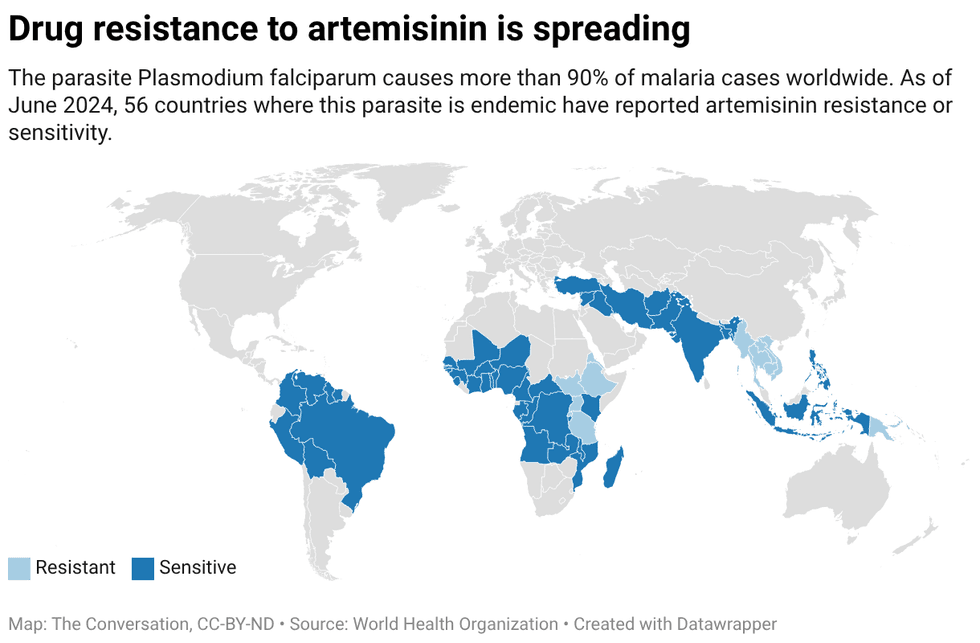

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Created with

Created with  Where to turn off autoplay in your account on Facebook’s website.Screen capture by The Conversation,

Where to turn off autoplay in your account on Facebook’s website.Screen capture by The Conversation,

A young teen cries while listening to music via

A young teen cries while listening to music via

A young couple waits in line at a coffee shopCanva

A young couple waits in line at a coffee shopCanva Gif of Eddie Murphy telling you to think

Gif of Eddie Murphy telling you to think